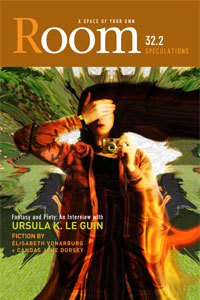

Speculations | 32.2

2009

Digital only; out of stock in print.

Women have been creating speculative stories for centuries. Long before 1818, when Mary Shelley published what is now hailed as the novel upon which science fiction was founded, women looked to the stars and dreamed of other worlds, shared tales of creatures and spirits they could not see, inexplicable phenomena, and parallel universes. In many ways, Shelley’s Frankenstein merely started the modern ball rolling for women’s speculative works, soon followed as it was by Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s fantastic story “The Yellow Wallpaper” in 1892 and in 1915 by her utopia “Herland”. Men, holding the power of the press, flooded the fantasy and science fiction genres with male-centered works, but in the latter half of the twentieth century, women burst onto the speculative scene in great number: Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Doris Lessing—too many to name here—produced works about women, works that examined women’s experience and solved problems women alone faced. They also created places and roles for women that did not exist in our world. Roles of freedom and power. Quite revolutionary, really, as many of these works fall under the label “science fiction”, a label with a pulpy reputation which must be defended even now, in the twenty-first century.

Over the past few months, we’ve read fantasies, ghost stories, fairy tales and fables, hard and soft science fiction, fantastic experiences, and stories about the slightly unhinged. I’ve found my definition of speculative literature broadening, deepening, with every offering. It has become clear to me that women’s speculations extend beyond genre and subgenre writing. Some of the works we’ve selected exhibit speculative tendencies yet have their feet firmly planted on Earth; others travel far.

True to the speculative tradition, this issue breaks some turf, starting with our commissioned writers, Élisabeth Vonarburg and Candas Jane Dorsey, two of Canada’s premier feminist science fiction writers. Ms. Vonarburg’s “The Museum of Impermanence” appears in its original French and in translation by Room’s Clélie Rich, marking the first time that Room has published a story in both of Canada’s official languages. Meanwhile, Candas Jane Dorsey’s “First Contact” explores the alien via a sexual encounter, going where no Room issue has gone before. In addition, we are thrilled to present a conversation with one of the most accomplished science fiction and fantasy writers of all time, Ursula K. Le Guin, in which she shares her thoughts on speculation, writing, and women.

Our diverse collection of tales includes Francis Boyle’s “EverPoppy” and Mary E. Choo’s “The Malcontents”, both dealing with themes of experimentation through science and magic, respectively. Also steeped in magic is Patricia Monaghan’s story of the healer, “Marjory’s Garden”, while Carolyn Clink’s “Sibling Rivalry” combines science and mythology.

We noticed a common element of water and water-bound entities in this issue, including Kelly Norah Drukker’s “Naimh” and the creative nonfiction “Torrent” by Lisa Gill, which, flowing here amidst the fantastic, could easily be mistaken for fiction. Kirya Marchand’s “the tell-tale heart”, and Chris Raves’ “Lost Side of a Pair” contain characters haunted by missing parts of themselves, while C. June Wolf’s “Dreamcatcher” presents two people who connect each other to the spirit world. Some never recognize such connections and lead a lone existence, as in Dawn Doucet’s “Industrial Kitchen.”

A number of humorous works lend wit and laughter to this issue, such as Mette Bach’s flash pieces, Eryn Hiscock’s swan Petra who falls in love with an unattainable suitor, Moneypenny’s side of the story as told by Kimmy Beach, and Michaela Roessner’s tale about a fisherman’s wife. Andrea Johnston taps into the escape and empowerment graphic novels provide girls in “Sending Alice to the Moon,” while Ayelet Tsabari’s “Fairy Shoes” reveals the role the fantastic plays for girls who need support.

We are pleased to present visual art pieces that capture the dynamic spirit and intelligence of speculative works. Tania Alexis Clarke’s “In My Living Room” toys with time and reality, her “Dusk Crawler” reveals another world and its unEarthly creatures, and Kristi Malakoff’s “The Case of the Phantom Schooners (detail)” and Stephanie Aitken’s “Oberland” portray universal possibilities.

In 1981, Room magazine (then Room of One’s Own) published an issue dedicated to science fiction and fantasy, edited by Susan Wood. Wood received three submissions each day, significantly more than I, nearly thirty years later, received. Does this mean our need for speculation has decreased? Has speculative literature been subsumed into mainstream literature? Perhaps neither, perhaps some of both; nevertheless, I see a need for literature that pushes beyond the constraints of our reality, our culture, and which creates new realities, different cultures, other worlds—literature that questions and liberates, poses solutions and provides an escape, for women, for the marginalized, the colonized. Kind of sounds like feminism, doesn’t it? And not unlike feminism, speculative literature has always given me a sense of hope and a feeling of belonging. And that’s what Room is all about. To those of you who may be embarking upon your first speculative experience and to those who know your way around the speculative universe, I say, Welcome, be unafraid, this is where you belong.

$10.00

Additional information

| Delivery | Canada, USA, International, Digital |

|---|

In this issue: Stephanie Aitken, Matte Bach, Kimmy Beach, Frances Boyle, Mary E. Choo, Tania Alexis Clarke, Carolyn Clink, Dawn Doucet, Candas Jane Dorsey, Kelly Norah Drukker, Maureen Egan, Lisa Gill, Eryn Hiscock, Andrea Johnston, Ursula K. Le Guin, Fiona Lehn, Kristi Malakoff, Kirya Marchand, Patricia Monaghan, Chris Raves, Clelie Rich, Michaela Roessner, Ayelet Tsabari, Elisabeth Vonarburg, Bronwen Welch, C. June Wolf